- Region

- Vega baja

- Marina Alta

- Marina Baixa

- Alicante

- Baix Vinalopo

- Alto & Mitja Vinalopo

-

ALL TOWNS

- ALICANTE TOWNS

- Albatera

- Alfaz Del Pi

- Alicante City

- Alcoy

- Almoradi

- Benitatxell

- Bigastro

- Benferri

- Benidorm

- Calosa de Segura

- Calpe

- Catral

- Costa Blanca

- Cox

- Daya Vieja

- Denia

- Elche

- Elda

- Granja de Rocamora

- Guardamar del Segura

- Jacarilla

- Los Montesinos

- Orihuela

- Pedreguer

- Pilar de Horadada

- Playa Flamenca

- Quesada

- Rafal

- Redovan

- Rojales

- San Isidro

- Torrevieja

- Comunidad Valenciana

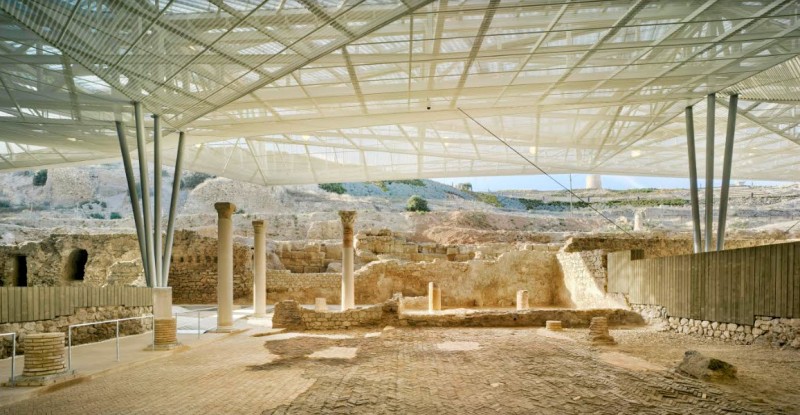

The Roman Forum District museum in the Molinete archaeological park in Cartagena

The remains of a thermal baths complex and a temple to the deities Isis and Serapis on the Molinete hill in Cartagena

When the importance of Carthago Nova, the Roman city which evolved into Cartagena, became clear during the 20th century one of the problems facing archaeologists as they attempted to discover more about life in the area 2,000 years ago was that much of the Roman conurbation lay beneath subsequent constructions, making it impossible to excavate.

This is the case, for example, of the Roman amphitheatre, which some believe may have been one of the largest and most important in the entire Empire: the exact location of the stadium is known, but on top of it are other buildings including the 19th century bullring.

However, one area which was clear for archaeological investigation was the Molinete hill, which now stands in the north of what is referred to as the “old” city centre, to the right of the pedestrian Calle Mayor for those strolling into town from the seafront. This was one of the five hills which stood as natural fortresses on the isthmus of land which Carthago Nova occupied – the era to the north and west was a lagoon, and with the harbour to the south this meant that water protected the city on three sides.

Those five hills were all named after mythological characters with the exception of what is now called the Molinete, which in Latin was referred to as the hill of the citadel of Hasdrubal (the Carthaginian founder of the city (Mons Arx Asdrubalis). The others were Mons Esculapii (the Hill of Asclepius, now the Monte de la Concepción), Mons Saturnus (the hill of Baal, on which there was a temple to the god of the storms and fertility, now Monte Sacro), Mons Aletes (the hill of Aletes, now Monte San José), and Mons Vulcanus, now known as Monte Despeñaperros and home to the campus of the Universidad Politécnica.

Nowadays, rather more prosaically, the Molinete takes its name from the mills which used to stand on its brow, the remains of one of which can still be seen.

During the period when Carthago Nova was at the peak of its prestige this hill was home to some of the most important buildings in the city, but in later centuries it became one of the more humble districts of Cartagena under the rule of the Visigoths and then after the Reconquista by Christian forces in the 13th century. Following that it was on the side of the Molinete hill and running along the city walls that the dwellings of the “Moriscos” were built: these were the former Muslims and their descendants who stayed in Spain after the Moors were finally expelled from the whole country in 1492, and their homes were humble single-storey shelters where the occupants spent only the hours of daylight. At that time the law forced them to return within the city walls at night to prevent them from going to the shore and communicating with the Barbary pirates from northern Africa, whose coastal raids kept the city in a state of continuous alarm.

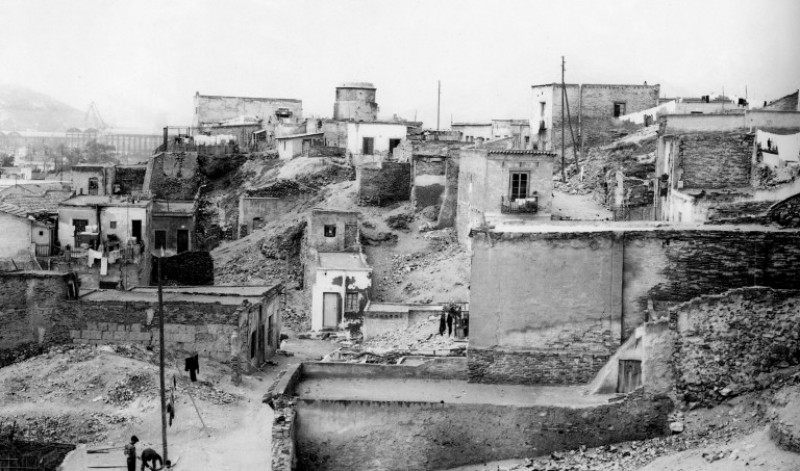

In later centuries a maze of narrow streets developed and the district became one of questionable repute but lively spirit, and there was even a kind of prosperity during the growth in mining activity and trade in the port in the late 19th century. But by the end of the 20th century the Town Hall allowed the ramshackle buildings nearest the top of the hill to be demolished, and this made it possible to undertake the first excavations.

What the archaeologists found here has made it possible for them to learn a great deal about Carthago Nova, piecing together a very clear idea of the layout of the Roman city and the elements it contained. The main part of the hill has been converted into a large, open air archaeological park, with public walkways and shaded areas opening up the top part of the site to the general public and more excavations on the southern face of the Molinete.

The resulting “Parque Arqueológico del Molinete”, which contains the Roman Forum district, is one of the largest in an urban location in Europe, occupying 26,000 square metres, although the area considered to be “on display” is rather smaller, on the southern side of the hill.

Thermal baths and peristyle

Various blocks or “Insulae” of the city of Carthago Nova have been uncovered, and in “Insula I” the remains of a thermal baths complex are protected under a modern roof alongside part of the atrium  building. This was presided over by a statue in Carrara marble carrying a “cornucopia” (or horn of plenty) and a basket of fruit in what is taken to be an allusion to the Pax Romana achieved by the Emperor Augustus after decades of civil war.

building. This was presided over by a statue in Carrara marble carrying a “cornucopia” (or horn of plenty) and a basket of fruit in what is taken to be an allusion to the Pax Romana achieved by the Emperor Augustus after decades of civil war.

Another decorative element found here is a painting representing a hunter.

In an era when most inhabitants of this city would have lived in homes without running water and sanitary facilities, public or semi-public baths provided washing facilities as well as being a place of social interaction and meetings. This thermal baths complex, built in the 1st century AD, comprises a characteristic succession of spaces: the frigidaria or cold rooms, also used as a changing room (apodyterium) which still has its original marble floor, the tepidaria or warm rooms, in which the heating system can still be seen, the sauna and the caldarium or hot room, which is located beneath modern day Calle Honda. The ovens are located in the Decumano, just across the road from the complex and visible from street level.

The entrance to the complex was via a colonnaded peristyle courtyard, a central porch surrounded by a covered walkway with columned supports. This led into the various rooms of the complex, as well as being a place of social interaction, in which those who were part of the corporation which owned the property could mingle, meet and conduct business.

This section of the site stands out for the state of preservation of its flooring, which is laid with bricks in a herringbone design, a popular style of the paving also known as “opus spicatum”.

The atrium building

The atrium building was built at the end of the 1st century BC to be the seat of a religious corporation devoted to the holding of ritual banquets in honour of the gods Isis and Serapis, who were worshipped in the temple alongside. Over the course of three centuries several alterations led to the modification of its original layout and in the last of these phases it was transformed into a residential building, with each room home to a family. The building remained in use until the late 3rd or early 4th century AD, when it was destroyed by fire.

Occupying an area of over 2,000 square metres, it was organized around a courtyard of columns with a stairway leading up to the upper floor. Opening out onto the central courtyard were four large rooms in which there are still vestiges of decoration: these were originally used for banquets, with the diners reclining on couches.

The building also contained a hall used for worship, where mural paintings imitating the effect of marble have survived and to one wall is attached an altar. Classrooms flank the entrance hall and the front was occupied by shops.

The most significant findings in the Atrium Building are a series of paintings depicting muses and the god Apollo, a text painted commemorating the reform of the building during the time of the Emperor Elagabalus in the year 218 AD and paintings of female masks framed within garlands.

The temple of Isis and Serapis

Higher up the hill are the remains of a Punic (or Carthaginian) temple dedicated to the goddess Atargatis, who was primarily a deity of fertility, while in the area known as “Insula II” there is a Roman temple devoted to Isis and Serapis, as indicated by inscriptions in stone. According to experts the condition of this temple is comparable to some of the finest of its kind, including those of Pompeii and Ostia in Italy and Baelo Claudia in Cádiz.

The remains excavated include the entire original structure of the temple, with three chapels and large underground water tanks related to the rituals performed in honour of the goddess. Built in the late 1st century AD, the building remained in use as a place of worship until the end of the 3rd century, when it was converted for industrial use.

Isolated from the surroundings environment and from people outside the cult by an imposing wall, the sanctuary was presided over by a small temple housing a sculpture of the divinity Isis, which is accessed by a staircase and whose façade consisted of four Ionic columns. Around the temple there was an open courtyard with porticoes on three of its sides, and to the rear there were three chapels where ceremonies were held with spaces reserved for the priests and the furnishings.

In the basement of the courtyard, in front of the temple, were four vaulted cisterns to collect rainwater for use in purification rituals such as the washing of the sculptures.

Between the temple and the chapels are the remains of an older cistern for storing rainwater. This was built in the Punic era at the end of the third century B.C. and was razed for the construction of the shrine.

The Decumanus

As long ago as 1968, when the old Guardia Civil barracks were demolished, a stretch of the Decumanus Maximus was found, along with the ovens that heated the tepidarium and Caldarium in the thermal baths, and the remains of a commercial area composed by a portico with shops. They were built in Republican Roman times and remodelled in the 4th century AD and there is an inscription dedicated to Numisius Laetus, a member of a powerful family in Carthago Nova, which would initially have been in the forum before it was re-used in building the wall of the thermal baths.

A similar stone bearing the name of a family member was found having been re-used in the construction of an annex at the monastery of San Ginés de la Jara and is now housed in the Enrique Escudero municipal archaeology museum.

OPENING TIMES

The opening times of the Roman Forum District museum are as follows:

High season (from 1st July to 15th September): every day of the week from 10.00 to 20.00.

Mid-season (15th March to 30th June and 16th September to 1st November): Tuesday to Sunday 10.00 to 19.00 (also open on the Monday of Easter Week).

Low season (2nd November to 14th March): Tuesday to Sunday 10.00 to 17.30.

The centre is closed on 1st and 6th January and 25th December and opens only in the morning on 5th January and 24th and 31st December.

Admission fees

Individual 5 euros, reduced rate 4 euros (for online bookings, under 12s, students, pensioners, groups of over 20 and others). Children aged 3 or under are admitted free of charge.

Address: Calle Honda, 11

Special facilities

In an effort to make tourism available and accessible for all visitors the Roman Forum District is equipped with stair lifts, special toilets and audio-visuals with sub-titles (in Spanish and English) for people with hearing disabilities. Access for guide dogs is permitted with the corresponding accreditation.

Click here for a summary of the period of Cartagena’s history which includes the centuries of Roman rule, or here for more information regarding the municipality.

For full information in English about the Cartagena municipality CLICK HERE

For full information about places to visit in Cartagena city CLICK HERE