- Region

- Vega baja

- Marina Alta

- Marina Baixa

- Alicante

- Baix Vinalopo

- Alto & Mitja Vinalopo

-

ALL TOWNS

- ALICANTE TOWNS

- Albatera

- Alfaz Del Pi

- Alicante City

- Alcoy

- Almoradi

- Benitatxell

- Bigastro

- Benferri

- Benidorm

- Calosa de Segura

- Calpe

- Catral

- Costa Blanca

- Cox

- Daya Vieja

- Denia

- Elche

- Elda

- Granja de Rocamora

- Guardamar del Segura

- Jacarilla

- Los Montesinos

- Orihuela

- Pedreguer

- Pilar de Horadada

- Playa Flamenca

- Quesada

- Rafal

- Redovan

- Rojales

- San Isidro

- Torrevieja

- Comunidad Valenciana

What is a Gota Fría?

Never underestimate the destructive power of the rain in Spain

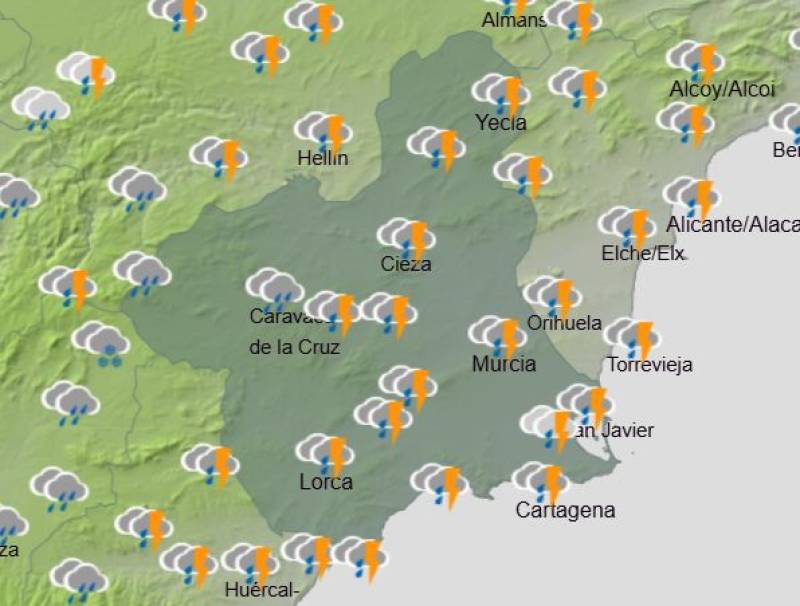

The Gota Fría is the popular name given in Spain to a meteorological phenomenon which can cause devastating flooding, especially in the south-east of the country along the Mediterranean coast, and which often occurs either generally or locally in the months of September and October.

The conditions which can lead to Gota Fría occurring are officially referred to by meteorologists in Spain as a DANA, or isolated high altitude depression, although it must be stressed that when a DANA warning is issued, this will not necessarily result in torrential storms and flooding at every point within a storm-warning area as these storms are highly localised and extremely difficult to pinpoint accurately.

Although the native population is accustomed to the heavy autumn storms, these can be terrifying for those unaccustomed to Spanish autumn weather, and can also be extremely dangerous for foreign visitors/residents who are unaware of the potential dangers, hence the need to know what constitutes a Gota Fría and why it is so dangerous.

Heavy storms are common throughout Spain in late summer and early autumn, but the Gota Fría is an especially violent kind of storm in which huge columns of cumulonimbus cloud rise to an altitude of up to ten kilometres before discharging their water content in torrential downpours. In one episode in 1987 over 1,000 millimetres of rain fell in 36 hours, including 400 millimetres in just 6 hours, and although this is reportedly the heaviest Gota Fría on record, countless others have caused chaos and claimed lives over the centuries in the Region of Murcia, the Balearics and the Comunidad Valenciana and Andalucía.

One of the most recent instances of flooding caused by these storms in the Region of Murcia was the one in Puerto Lumbreras and Lorca in 2012, during which 13 people lost their lives, and in 2014 there were fears of similar devastation in Camposol when the rambla which runs through the development burst its banks. Fortunately, although the damage done to roads and properties was considerable, no human lives were lost.

What causes a Gota Fría to develop?

Not all torrential downpours are caused by DANAs, and not all DANAs produce torrential downpours, and to understand this it is necessary to understand the basic circumstances which have to coincide for a Gota Fría effect to be produced.

The main factors which contribute to a Gota Fría storm forming are four-fold. Firstly, the warmer the water of the Mediterranean, the more likely it is that a violent storm of this nature could form.

Secondly, unstable air is required at low altitudes, and thirdly, a mass of cold air needs to be present in the troposphere, at an altitude of between 5,000 and 10,000 metres. If all these factors coincide and there is a prevailing wind, a Gota Fría storm forms.

This is because when the sea is warm it produces a large quantity of warm vapour, just like the condensation produced by a warm bath. If this vapour then comes into contact with a low pressure area or a cold front and there is a large body of cold air at high altitude, the instability in the atmosphere increases the higher it goes. The vapour rises, carried by this upward airstream, and condenses when it hits the cold air, forming a cloud.

Within just a couple of hours a column of cumulonimbus of over ten kilometres in height can be formed, guaranteeing heavy rain, normally accompanied by lightning and hailstones.

Due to the importance of the vapour from the sea in forming this kind of storm, it generally happens in coastal areas, but the same phenomenon can also occur inland as the clouds gather over mountainous areas.

The arrival of a Gota Fría is notoriously difficult to forecast with any accuracy until it actually begins to form: the best that can be done is to gather information showing that the factors which lead to its formation are present and warn of the possibility that all of the elements required to create a Gota Fria are about to coincide.

It must be pointed out that a Gota Fria can be highly localised, pulverising a very small area, while neighbouring villages don´t even see a drop of rain.

The video below shows the dangers of ramblas. When rain has fallen inland it can rush down the ramblas in a violent wave as this video clearly shows, a wall of water of water clearing everything in its path. Image: @Zelda_79 @PedroCFernandez

Storm damage

The damage caused by these downpours is not limited to the area in which the rain actually falls, it can sometimes be most serious in locations where not a drop of water has actually been recorded.

This is because of the nature of the landscape: the mountains and hills are generally steep and rocky rather than gentle and covered in soil, and as a result all or nearly all of the water which falls in them runs off onto lower ground rather than being absorbed into the soil. In fact, what soil there is tends to be washed away by the rain, and ends up in the nearest valley: for this reason, large areas of eastern and south-eastern Spain are fertile flood plains.

For example, the devastation in 2012 in Puerto Lumbreras, which lies in the Guadalentín valley and flood plain, was caused to a large extent by the rain which fell in the mountains further inland. This rain rushed down the ramblas, or natural dry river-beds which act as floodwater channels, and accumulated rapidly on the plain.

Apart from the damage and the threat to human life which is caused by the water cascading down these channels with a force which is barely credible for those of us who have never seen it, the destruction can also extend to bridges over the rambla and, above all, the agriculture on the flat and fertile flood plains.

Again, the Puerto Lumbreras flood in 2012 is a good example. Through the centre of the town runs the Rambla de Nogalte, a wide channel which was formed over the course of millions of years by floodwater running down from the mountains to the north-west, and bridges, roads and other infrastructures all suffered in the urban area.

The effect on the local economy, though, was greater on the flood plain, where thousands of cattle were lost and crops were flooded. This explains why many of the houses on this flat land are built on “stilts”, with the living area effectively on the first floor.

In a previous Gota Fría on 19th October 1973 there were 88 victims in Puerto Lumbreras, and the widespread destruction in the town centre led to the course of Rambla Nogalte being turned into a permanent canal.

Ramblas

The meaning of the world “rambla” in the south-east of Spain is very different from in Catalunya, where it refers to a tree-lined avenue as in the centre of Barcelona.

A rambla in the south-east is a dry river-bed or floodwater channel, and we see them every time we drive around without really paying much attention to them. They are sometimes known in English as arroyos (another Spanish word which generally means “stream”), dry creeks or gulches.

They are unspectacular, unremarkable and harmless features of the landscape almost all of the time, and can remain dry for years. In the Rambla de Benipila in Cartagena there used to be football goalposts for impromptu kickabouts, and in many towns and cities the ramblas are used by locals as free car parks.

In some parts of Spain, unscrupulous Town Halls have even allowed residential properties to be built in or next to ramblas over the last few years.

All of these uses for ramblas are absolutely fine, of course, until it rains. As soon as that happens, the danger of being in or near a rambla must not be underestimated.

Every autumn we see instances of cars, street furniture and, in the most tragic cases, people, being washed down ramblas by walls of floodwater as flash floods suddenly fill these normally dry channels with rushing water. In particularly severe episodes the ramblas can even overflow, especially when they have not been cleared of undergrowth, litter and trees, and when this happens the devastation spills over onto the land or streets alongside.

A miniature version of this effect can be seen at many beaches, where increased residential development has led to the soil being covered with cement and tarmac. This means that when it rains all of the water follows the most direct route possible down to the shoreline, and as a result gulleys are quickly eroded into the sand, often taking wooden walkways and foot showers with them to the sea. This damage is of course trivial in comparison to a major flood, but it is a reminder of the destructive power of water.

Precautions to take if the gota fría or heavy rain is imminent

The most important advice to bear in mind if heavy storms are forecast, or indeed if the skies suddenly cloud over ominously and unexpectedly, is to use common sense, and first and foremost this means STAY AWAY FROM RAMBLAS.

Ramblas can become dangerous even in areas where not a drop of rain has fallen as the water flows down from the mountains inland – in recent years those attending a market in a rambla in the province of Alicante were surprised by a flash flood despite it not having rained, killing several tourists – and the danger to anyone nearby should never be under-estimated.

No exact death toll has ever been reached for the disaster in Bolnuevo in 1989, when part of the campsite next to the Rambla de las Moreras was washed away and tents and caravans were swept into the Mediterranean.

The importance of keeping a clear head can be illustrated with an anecdote from 28th September 2012, when the headlines quite rightly focused on the disaster in Puerto Lumbreras. On the same day an extremely violent downpour began in Molina de Segura at around 3 o’clock in the afternoon, and this writer decided to move his car from the waste ground where it was parked close to the River Segura.

Had the vehicle in concern been a military amphibious landing craft this could have been a good decision, but unfortunately it was in fact a Peugeot 207, and as the rain rushed down from the hillside on which Molina stands the streets were knee-deep in water within minutes. As the Peugeot gamely struggled to reach higher ground the water rose almost to the top of the wheels, and pavements, drain covers and other obstacles were hidden from sight.

Fortunately there were no water channels or drainage ditches alongside this stretch of road as they would have been completely obscured as the entire road resembled a rapidly flowing river. Every year people die when their vehicles leave the road and fall into ditches which they are unable to see, and are then swept out into the main current of the ramblas and usually out to sea. Exiting these vehicles is virtually impossible once they are in fast flowing water.

The driver’s mind was by now completely frazzled as he envisaged headlines along the lines of “Foolish Englishman lost in Molina flash flood”, but by a combination of the Peugeot’s reliability and some huge slices of luck he eventually made it to the top of the hill in the east of Molina and lived to tell the tale.

The moral of the story is really simple: never underestimate the power of the gota fría and the flash floods it brings. If heavy rain is forecast keep away from areas which are prone to flooding, especially ramblas.

Once the rain starts, unless you find yourself in a clearly dangerous location avoid using the car, stay inside and wait until the storm is over. Remember that the insurance company will cover any damage to the car, and let nature take its course while keeping well out of the way!

Other advice issued by fire brigades and the police include the following:

IN THE HOUSE

Carry out regular reviews of the state of roofs, Windows and guttering.

Keep important documents in a safe, dry place.

Remove toxic products (such as herbiucides and pesticides) from places where wáter could accumulate.

Be sure to have a torch and a first aid kit in the house.

If flooding seems likely, cut off the electricity supply.

In cases of sudden flooding head for high ground or the highest part of the house.

ON THE ROADS

Avoid driving, especially at night.

Carry out regular checks on the brakes in your vehicle.

Avoid driving through flooded areas, even if you know the road well. If it is absolutely necessary, do so in first gear.

Head for high ground.

Park away from walls and fences.

If the water rises above axle level (or knee-high), abandon the vehicle and wade to higher ground.

Full beam can be used as a request for help at night, using Morse Code for SOS (three long flashes, three short, and three long again).

But above all, keep an eye on the weather reports, and take Gota Fria warnings seriously.