- Region

- Vega baja

- Marina Alta

- Marina Baixa

- Alicante

- Baix Vinalopo

- Alto & Mitja Vinalopo

-

ALL TOWNS

- ALICANTE TOWNS

- Albatera

- Alfaz Del Pi

- Alicante City

- Alcoy

- Almoradi

- Benitatxell

- Bigastro

- Benferri

- Benidorm

- Calosa de Segura

- Calpe

- Catral

- Costa Blanca

- Cox

- Daya Vieja

- Denia

- Elche

- Elda

- Granja de Rocamora

- Guardamar del Segura

- Jacarilla

- Los Montesinos

- Orihuela

- Pedreguer

- Pilar de Horadada

- Playa Flamenca

- Quesada

- Rafal

- Redovan

- Rojales

- San Isidro

- Torrevieja

- Comunidad Valenciana

Nuestra Señora de la Mercedes, ARQUA Cartagena

14.5 tons of coinage was recovered from this vessel which sunk in 1804

The ARQUA museum of subaquatic archaeology in Cartagena has played an essential part in the process of conserving and restoring not only the 574,553 pieces of gold and silver coinage, weighing 14.5 tons, recovered from the sunken Spanish frigate, Nuestra Señora de la Mercedes, but also in recovering and conserving other artefacts from the vessel.

Part of the static exhibition in the museum is dedicated to the wreck and the museum continues to collaborate in the recovery of the remaining artefacts, the exploration of the wreck-site as well as undertake conservation work in its laboratory facilities.

Nuestra Señora de la Mercedes was sunk by British ships on 5th October 1804 just off the coast of Cape St Mary, Portugal; having successfully crossed the Atlantic from the Spanish colony of Peru, laden with coinage destined to pay for Spain´s wars in Europe when she was attacked by a British squadron who were unaware of the great treasure she carried.

She had set sail from the port of Montevideo in Uruguay on the 9th August 1804, having first stopped off at Lima to load the bulk of the coinage, with her final destination Cádiz, accompanied by three other vessels: the Fama, Medea and Santa Clara.

Close to the Portugese coast she was ambushed in the early hours of the morning on the 5th October by four British vessels, their original intention being to push the Spanish vessels into a British port, a violation of the 1802 Treaty of Amiens signed in 1802. Upon refusal, the British opened fire.

During the ensuing battle, the Battle of Cape Santa Maria, the 34 gun frigate was sunk, shattering after an explosion in the powder magazine, with 275 crew lost, together with her cargo of coinage. The three remaining vessels were escorted into Plymouth by the British, but the 14 tons of coinage had disappeared to the bottom of the sea.

200 years later the wreck was located by American marine exploration company, Odyssey, who recovered the artefacts from a depth of 1100 metres without the knowledge of the Spanish government, baptising their recovering operation “Cisne negra, Black Swan”.

The company officially announced that it had recovered the coinage from what it called the “Black Swan Colonial period site” in May 2007, stating that “there was no apparent hull of a shipwreck or other sufficient evidence at the site to conclusively identify a vessel from which the treasure may have originated” and that the coinage was found in an area where “a number of Colonial period ships were believed to have sunk.”

Odyssey said that the “leading hypothesis suggested the coins and artefacts discovered at the "Black Swan" site may have been associated with the Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes,” stating that “72% of the coins transported aboard the Mercedes were owned by private merchants and not the Spanish government” thus claiming the coinage as treasure.

The Spanish government, however, insisted that the company had deliberately set out to find this vessel, knowing the approximate location where it had gone down in 1804. Original loading documents and records from the state mints where the coins had been stamped were all retrieved from state archives, and other personal artefacts belonging to crew members which had been found during the recovery operation, were presented by the Spanish government as indisputable evidence that the coins had come from the Mercedes in the ensuing court battle which followed.

The Spanish government maintained that this vessel had been, and still remained, the property of the Spanish state, and for that reason its cargo could not be claimed as treasure by the salvage company.

Odyssey attempted to negotiate a settlement in which it was allowed to retain a percentage of the coinage to cover expedition costs, but all attempts at reaching an agreement were rebuked by the Spanish government, who insisted that all of the artefacts recovered be returned in their entirety to Spain.

Odyssey, meanwhile, had flown the coinage to America out of Gibraltar without the knowledge of the Spanish government, who had pursued the Odyssey vessel into Algeciras, thinking that the currency was still on board.

An acrimonious series of court actions began, concluding in 2012 when the US Federal Court dismissed the case upon determining it did not have jurisdiction and ordered the coins and artefacts be turned over to Spain.

The coinage was initially sent to Madrid, then transferred to the ARQUA in Cartagena, which has specialist laboratories able to undertake the long-term conservation of the coinage, believed to be the largest haul of coinage ever recovered.

The bulk of the coinage arrived in Cartagena during December 2012 and the remainder of the artefacts, including wood, ceramics and personal items belonging to crew and passengers, in July of 2013.

Much of the coinage was fused together in lumps, and sophisticated visual detection techniques ascertained that it comprised 309.396 individual coins, 212 in gold, 309.184 in silver, and 265.157 pieces of metal plate.

Most of the coinage is Spanish minted belonging to the Bourbon Monarchs ( Carlos III and Carlos IV), issued between the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, the latest being dated 1804, the year in which the frigate was sunk. One of the most interesting pieces in the exhibition housed at the ARQUA museum is one piece of eight which co-incided with the end of the reign of Carlos III, bearing his profile, but the name of Carlos IV, obviously minted during the transition period between the two monarchs.

The coinage was minted in the American viceroyalties at the Royal Mints of Lima, Potosi, Popayan and Santiago de Chile, but the most abundant are those of Carlos IV, minted in 1803 in the mint at Lima. Most are silver pieces of eight, whilst the gold coinage comprises pieces with a value of eight escudos (pieces of eight).

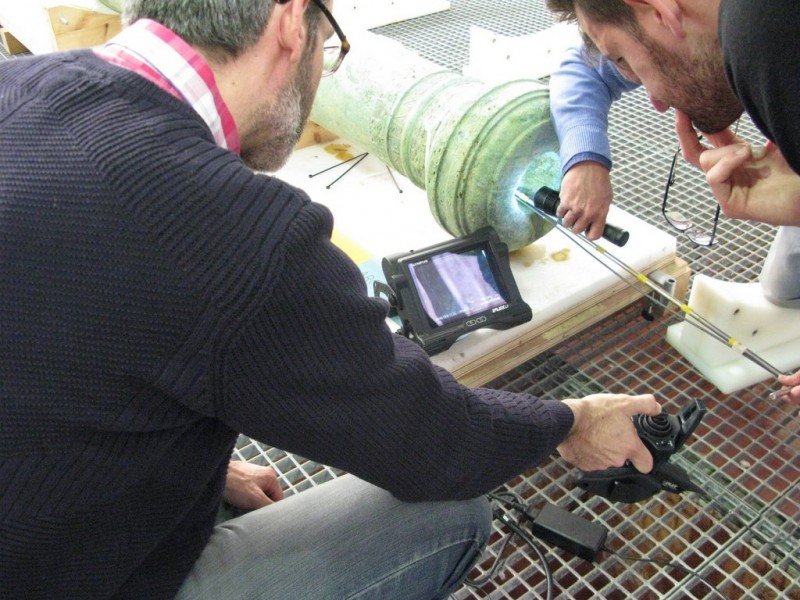

Conservation work was undertaken at the ARQUATec laboratory in Cartagena, using a variety of chemical solutions to first stabilise the coins before deciding whether to isolate each coin or leave them fused into smaller groups, before cleaning.

The condition of each of the coins is determined by the environment surrounding them, so some have been affected by contact with copper, or iron, whilst others were moulded by pressure and weight, enclosed by sand and other sacks weighing down on top of them.

The coins can be separated using chemical solutions, different solutions for different problems, then cleaned using a process of electrolysis. The total cleaning time for each coin is a matter of days, but the problem faced by lab staff is the sheer volume, this being the biggest haul ever tackled by laboratory staff anywhere in the world.

In May 2014, 33,000 coins were sent to Madrid to form a temporary display in the national archaeological museum, the Museo Arqueológico Nacional (MAN) and a smaller display in the Naval Museum in Madrid.

A further 8000 coins were selected for display in the ARQUA, Cartagena, some cleaned back to their original condition, the majority having undergone a stabilisation process but still tarnished and others still fused into the original sack shaped lumps in which they were discovered.

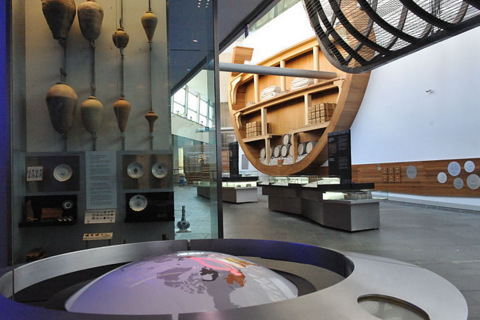

The ARQUA exhibition

The ARQUA exhibition

The display in the ARQUA begins with an examination of the trade routes operating during the nineteenth century, visitors able to view the different shipping routes via an interactive map, next to a case showing some of the trade goods being shipped. Porcelain is one of the most important luxury goods, a commodity which was not produced in Europe until the middle of the eighteenth century and could only be purchased from the Far East. As the Industrial Revolution changed the demography of wealth distribution, the rapidly burgeoning middle classes created vast demand for luxury goods, porcelain, spices and cloth amongst them.

The importance of spices as trade goods is highlighted by a display on the opposite wall, in which a series of drawers set into the wall can be opened to smell the different spices carried on these trade routes.

On the same wall the rudimentary navigation aids used by mariners to traverse the oceans are displayed: cord which was knotted and unravelled behind the vessel to calculate the distance covered and the speed of the vessel ( leading to the knots calculation of speed still used today) and hourglass, as well as sextant and more modern compass. A cross section of the original ship has also been recreated on the same wall, showing the size of the vessel and also the manner in which the cargo was loaded.

Much of this was in sacks, placed inside wooden crates, a method which can be seen in a model housed in the central display cases, which are also home to the coinage itself, along with some of the personal possessions of the mariners themselves and copies of documents showing both the original consignments loaded onto the vessel along with accounts of the battle in which the Mercedes was sunk.

The exhibition concludes with a video showing the restoration process and reminding visitors of the importance of preserving the marine patrimony which still lies on the seabed, as yet undiscovered.

Although undeniably salvage companies such as Odyssey are responsible for valuable historical discoveries, government bodies and marine archaeologists are always critical of the manner in which these sites are excavated by commercial companies. Although in this case Odyssey state that the site was mapped and the excavation meticulously documented, the ARQUA museum director likened their methods to “knocking down a cathedral to get to the statues inside”.

Marine archaeologists have long called for greater protection for Spanish wrecks, there being literally thousands of vessels beneath the waters along the Spanish coastline. In one interview it was said that " there is more gold sunk in the Gulf of Cadiz than in the Bank of Spain, " estimating that there are at least 850 hulls in the bay of Cádiz alone, many known to contain vast quantities of coinage.

This is the first case of a government winning a legal battle against a marine exploration company for ownership of a cargo recovered, and although it is a source of great pride for the government to recover this treasure, has also prompted fears in some quarters that the victory will do more long-term damage to the prospects of marine archaeologists finding and properly excavating wrecks before the salvage companies, the loss of the treasure encouraging them to find and strip vessels without their discovery being properly reported and recorded.

Since the original haul was recovered from Odyssey the ARQUA has continued to support the project to map the site archaeologically and recover other historically important artefacts.

Three camapigns have taken place in 2015, 2016 and 2017.

The first campaign took place in August 2015, the oceanographic vessel Ángeles Alvariño, equipped with an ROV rapidly confirming the exact positioning of the shipwreck and undertaking a detailed bathymetric multi-beam survey of the site, the result of which is a virtual grid of an area covering 20,000 metres and corresponding video data.

Although the site is more than 1100 metres below the surface there is a strong bottom current which limits the accumulation of sediment around the artefacts, so in spite of the fact that items such as a dinner set had sunk more than 200 years ago, the outline shapes of cutlery and plates could still clearly be identified on the seabed.

During this first expedition the team was able to produce a detailed map of the site and several objects were retrieved by the ROV, some of which have now completed a process of restoration and can be seen in the museum.

In 2016 the team returned to continue surveying the site and in 2017 undertook the task of extracting two large cannons from the silt

.The two cannons were named La Santa Bárbara and la Santa Rufina. The first weighs 2.8 tons, measures 4.3 metres in length and was made in 1586, commissioned by Fernando de Torres y Portugal, Viceroy of Perú between 1585 and 1589. The second is dated 1601, measures 3.8 metres in length, weighs two tons and was ordered by Luis de Velasco y Castilla, Viceroy of Nueva España (México) and Peru (from 1595 to 1603).

The two cannons are now undergoing a restoration process in the ARQUAtec laboratories and will be ready for display around 2020.

ARQUA Cartagena

The ARQUA contains an interesting collection of artefacts from a number of wrecks recovered along the Murcian coastline, as well as a static display relating to the whole subject of marine archaeology.

Click for full information about the ARQUA, as well as map, opening times and entry fees, ARQUA Cartagena