- Region

- Vega baja

- Marina Alta

- Marina Baixa

- Alicante

- Baix Vinalopo

- Alto & Mitja Vinalopo

-

ALL TOWNS

- ALICANTE TOWNS

- Albatera

- Alfaz Del Pi

- Alicante City

- Alcoy

- Almoradi

- Benitatxell

- Bigastro

- Benferri

- Benidorm

- Calosa de Segura

- Calpe

- Catral

- Costa Blanca

- Cox

- Daya Vieja

- Denia

- Elche

- Elda

- Granja de Rocamora

- Guardamar del Segura

- Jacarilla

- Los Montesinos

- Orihuela

- Pedreguer

- Pilar de Horadada

- Playa Flamenca

- Quesada

- Rafal

- Redovan

- Rojales

- San Isidro

- Torrevieja

- Comunidad Valenciana

article_detail

Date Published: 20/01/2014

Moratalla history

Since prehistory Moratalla has been home to makind due to its abundant natural resources

Moratalla has a rich and varied history, its abundant natural resources exploited by settlers throughout its history, a constant stream of inhabitants leaving behind a vast catalogue of archaeological sites, scattered across this vast municipality, which includes a range of important sierras, woodlands and natural water sources.

Moratalla has a rich and varied history, its abundant natural resources exploited by settlers throughout its history, a constant stream of inhabitants leaving behind a vast catalogue of archaeological sites, scattered across this vast municipality, which includes a range of important sierras, woodlands and natural water sources.

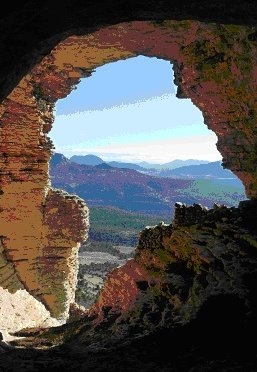

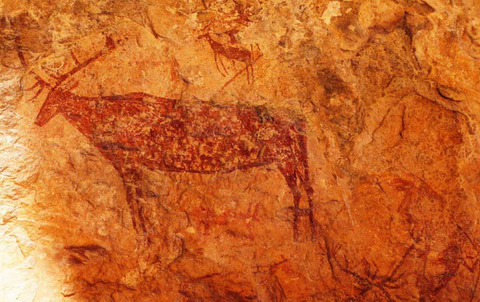

Even today, the attractions of the municipality of Moratalla include high mountains, valleys, rivers and plentiful hunting, and it was these same features which attracted the first settlers to the area, as can be seen from the cave paintings and remains of stone-working, which highlight the presence of the primitive hunters who roamed the countryside here.

Among the cave settlements discovered are those at Cañaica del Calar, Fuente del Sabuco, Molino de Capel, Andragulla, La Risca and El Molino, making Moratalla the home to over half of the cave paintings known to exist in the Region of Murcia. All of them are included in the cave paintings of the Mediterranean coastal area which were declared a part of world heritage by UNESCO in 1998.Although the paintings are not on the scale  of some of the better known cave paintings in Spain, their importance cannot be underestimated and the town has a museum dedicated to the Arte Rupestre, or rock art for which the area is famous.

of some of the better known cave paintings in Spain, their importance cannot be underestimated and the town has a museum dedicated to the Arte Rupestre, or rock art for which the area is famous.

In the Neolithic Age the first shepherds and farmers built their homes in settlements which were chosen for reasons of defence and water supply, in other words on promontories or walled hills, close to sources of fresh water, of which Moratalla has an abundance. From this time there are fortified settlements, megaliths and dolmens (for example at Bagil) in the municipality of Moratalla, and tools and utensils have also been found at a number of locations.

The natural communications routes of Moratalla (particularly the high ground and the lower area of Las Cañadas) were dotted with settlements which were established close to springs and on land which was easy to defend. One settlement from this period is Villaricos, close to Calar de la Santa, and there are also hilltop towns at Moratalla la Vieja and Villafuerte.

The Iberians

Remnants of the important Iberian culture which was prevalent in this part of Spain between the 5th and 1st centuries BC ( click Iberians) can be seen at the sites in Los Castillicos and Molinicos, and at Cuevas de Zaén, Priego, Benizar and La Nariz. Some of the rural villages of the municipality, including El Sabinar, the castle of Moratalla and the castle of Benizar, were built on top of old Iberian settlements, and it is highly likely that if further research is carried out then more evidence of the Iberian settlements will be uncovered. There is significant evidence of Iberian settlement in nearby Mula, where the El Cigarralejo archaeological site indicates a substantial Iberian presence in the area. Caravaca de la Cruz also has important Iberian remains.

The Romans

The Iberians disappeared as a definable culture following the Roman invasion, when Scipio defeated Hannibal in 209 BC, taking the city of Cartagena from the Carthaginians, and the Roman occupation of what they called Hispania began. Local tribes gradually absorbed the influences of the Romans and Moratalla was Romanized, as can be seen from evidence in almost the whole of the municipality. Roman “villas” were scattered all over the countryside, including those at Ulea, Los Granadicos, Andrevía and Víllora. The Romans took advantage of the salt flats of El Zacatín and the sulphur mines of Salmerón, and among the monuments they left behind is the Puente de Hellín, the bridge over the Alhárabe river which connected Moratalla to Albacete and which is still used today. Oil lamps, crockery, ceramics and coins have also been found.

The Iberians disappeared as a definable culture following the Roman invasion, when Scipio defeated Hannibal in 209 BC, taking the city of Cartagena from the Carthaginians, and the Roman occupation of what they called Hispania began. Local tribes gradually absorbed the influences of the Romans and Moratalla was Romanized, as can be seen from evidence in almost the whole of the municipality. Roman “villas” were scattered all over the countryside, including those at Ulea, Los Granadicos, Andrevía and Víllora. The Romans took advantage of the salt flats of El Zacatín and the sulphur mines of Salmerón, and among the monuments they left behind is the Puente de Hellín, the bridge over the Alhárabe river which connected Moratalla to Albacete and which is still used today. Oil lamps, crockery, ceramics and coins have also been found.

The Moors

The Roman Empire had disintegrated by the fifth century, leaving Spain vulnerable to invasion, and during the next two centuries a series of Goths, Vandals and Visigoths swept down through Spain. There was certainly a significant Visigoth population at nearby Cehegín, as is testified by the presence of the Begastri city remains just outside the main town, although little is known about Moratalla itself under the Visigoths.

The Roman Empire had disintegrated by the fifth century, leaving Spain vulnerable to invasion, and during the next two centuries a series of Goths, Vandals and Visigoths swept down through Spain. There was certainly a significant Visigoth population at nearby Cehegín, as is testified by the presence of the Begastri city remains just outside the main town, although little is known about Moratalla itself under the Visigoths.

Roman run farms appear to have been abandoned, and left to ruin, and the population fell dramatically in the 5th and 6th centuries AD, due to the dangerous situation created by the constant wars between rival Visigoth tribes and the dangers of further invasions from the North. Begastri was certainly reinforced and was a substantial walled defensive settlement, although was unable to offer shelter to residents as far away as Moratalla.

Equally little is known about the arrival of the Moors who first invaded Spain in 711 and gradually moved down until they totally dominated southern Spain. The Moors were undoubtedly settling in the area well before the first documented reference to Moratalla under the Moors in the year 1147, when Ibn Hilal revolted against the rule of his cousin Ibn Mardanix, the king of the Taifa of Murcia. By this point there was a fortified castle in the location of the current castle, although it is not known when construction of the castle was actually undertaken. This reference comes from the 14th century historian al-Jatib, who tells how Yusuf Ibn Hilal began his uprising against Ibn Mardanix in the area of Castellón, and took control of three castles which became his strongholds. One of these castles was Moratalla. However, Ibn Mardanix (also known as the “Rey Lobo”, or Wolf King), captured the rebel and demanded that he hand back the castle, under the threat of having an eye removed. Ibn Hilal refused, and the threat was carried out. Infuriated, the Wolf King led Ibn Hilal to the walls of the castle, and addressed the prisoner’s wife, telling her that if she didn’t hand over the castle he would take out her husband’s other eye. She also refused, and the rebel was left completely blind.

It is known that after the initial Moorish invasion and conquest of Hispania various Berber clans settled in the land around Moratalla, occupying areas like Mazuza, Priego, Benizar, Zaén, Bagil, Zacatín, Inazares and Benámor, among others, all names of settlements which still bear the names of the Moorish farmers who founded them. All of these country communities came under the jurisdiction of the Hisn (fortress) of Muratalla (as the Moors referred to the town), which was the administrative and military headquarters of the region. This geographical and administrative division is mentioned by various Moorish geographers, including al Idrisi, in their descriptions of the Cora de Tudmir.

Following the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212, the kingdom of Al-Ándalus began to go into decline, and the Military Order of Santiago, spreading the Reconquist from the North of Spain, took advantage of the weakness of the Moors, conquering Segura de la Sierra. In recognition of their feat King Fernando III of Castile donated Segura and all the surrounding territory to the Order on 21st August 1242, and on 5th July 1243, when the order was officially confirmed by a charter signed by Prince Alfonso (the future Alfonso X of Castile), it was explicitly stated that this territory included the Mudéjar settlements of Moratalla, Priego and Benizar, which depended on Segura de la Sierra.

The Later Middle Ages

Once back under Christian control the Villa and Encomienda of Moratalla was created in 1245 when it was segregated from Segura de la Sierra, although the Islamic Mudéjar population remained.

Once back under Christian control the Villa and Encomienda of Moratalla was created in 1245 when it was segregated from Segura de la Sierra, although the Islamic Mudéjar population remained.

Although attempts were made to bring Christian settlers into the territory to replace the Muslim farmers who had either left of their own will, been killed during the Reconquist or were subsequently forced out after the Mudejar rebellion in 1266, the population remained low and many areas were abandoned due to the insecurity of life so close to the frontier with the kingdom of Granada, the last remaining Moorish Kingdom. The Order of Santiago offered advantageous conditions to anyone who worked the land in 1246, but nobody was willing to take the risk of inhabiting frontier territory despite the incentives offered.

The fears of the people were far from unjustified. Moorish raids were frequent in the mountains around Moratalla, and the loss of Huéscar in 1324 brought the frontier even closer. The situation improved somewhat when Diego de Soto, the chief administrator of Moratalla and a man with profound knowledge of the Moors’ language and customs, took part in peace negotiations in Granada, and when Huéscar was reconquered by the Christians in 1488 the frontier again moved away from Moratalla. This brought the ploughs, farmers and crops back to the fields around the town.

In 1493 a papal bull issued by Innocent VIII decreed that the land controlled by the Order of Santiago came into the possession of the Crown of Castile, and in Moratalla it can be considered that this event marked the end of the Middle Ages.

On 19th April of the same year an event occurred which was to change the religious way of life of the people of Moratalla and is still celebrated in the fiestas held in the town today: in the mountains of Benámor a woodcutter or farmworker named Rui Sánchez saw a vision of Jesus Christ, and on the spot a church called the Casa de Cristo was built. ( Casa de Cristo - house of Christ) This church still remains today, along with a more substantial building which has some of the most stunning views over the Moratalla countryside and is a popular spot for walkers wishing to explore the surrounding countryside. This apparition was to become the  focal point of the town’s religious fervour, and Jesucristo Aparecido was adopted as the patron saint. Meanwhile the population grew from 300 in 1507 to 500 in 1524 and 534 in 1530.

focal point of the town’s religious fervour, and Jesucristo Aparecido was adopted as the patron saint. Meanwhile the population grew from 300 in 1507 to 500 in 1524 and 534 in 1530.

This growth continued during the 16th century, and as a result the face of the town changed. Houses had been grouped around the castle, but now they spread to new areas, occupying almost the whole of the area which comprised the urban centre until the end of the 19th century. The Concejo arranged for water to be brought to El Cañico, which was in the centre of the town at the time, and other public taps and fountains were installed in different areas, while streets were also renovated.

Encouragement was given to those who grew grapes, both in the Huerta and in Las Cañadas, and excellent wine was produced. Olives, mulberry trees, hemp and fruit were also grown, and indeed part of the olive-growing area is still used today. Potatoes and corn were introduced to the countryside, although the lack of water limited their spread, and it was partly due to this that the Concejo ordered the construction of the bell-tower in 1535, so that the farmers’ irrigation times could be better organized. The following year saw the installation of the clock, which was made by Sabañán, but it turned out that the bells could not be heard in all the Huerta, so in 1592 the tower was made higher.

Livestock farming became even more important than previously, as is shown by the creation of a butchers’ guild in the town, and the pasture land in the mountains was home to goats and sheep. Moratalla became the centre of local livestock farming, and a prestigious market developed.

The 16th and 17th Centuries

This flourishing local economy proved to be attractive to religious orders, and following the provision made by Felipe II in 1566, the Concejo authorized the establishment of the Convento de San Francisco, giving over the Ermita de San Sebastián and the land around it to the Franciscans. Not long afterwards, in 1589, the Concejo allowed the Orden de la Merced to take up residence in the Ermita Santuario Casa de Cristo.

This flourishing local economy proved to be attractive to religious orders, and following the provision made by Felipe II in 1566, the Concejo authorized the establishment of the Convento de San Francisco, giving over the Ermita de San Sebastián and the land around it to the Franciscans. Not long afterwards, in 1589, the Concejo allowed the Orden de la Merced to take up residence in the Ermita Santuario Casa de Cristo.

The Order of Santiago continued to dominate the political, judicial, ecclesiastical and economic structure of Moratalla, despite the papal bull issued by Alexander VI in 1499 which made the King the head of all institutions, over and above the leaders of the religious orders. The castle was still treated as a fortress of war, but administrative matters were now dealt with in the Casa de la Encomienda, in what was then known as the Calle de Tercia (the modern day Calle García Aguilera). This became the centre of the town. The most prominent inhabitants became “regidores”: initially there were twenty of these municipal officers, but the number was later reduced to twelve, who formed the corporation which was headed by the mayor.

Judicially, Moratalla fell under the authority of the courts of Villanueva de los Infantes (Ciudad Real), but the sheer distance from these courts meant that the system was excessively slow. This caused numerous protests, and in 1540 a permanent legal officer was installed in Caravaca, but following doubts over the honesty of those involved in the Caravaca courts Felipe II ordered a return to the authorities in Villanueva de los Infantes.

In 1535 there was another religious apparition in Moratalla: this time the Virgin Mary (“la Rogativa”) appeared to a young shepherd named Ginés Martínez. The church of Santa María de la Asunción is now one of the most important monuments in the town, and it was in the 16th century that the most important extension work was undertaken on the building. The influence of the architects Francisco Florentino and Juan de Marquina can be seen, and the work was supervised by Pedro de Antequera. The ashlar stone was fashioned by the mason Juan Inglés, and in 1563 the walls of the square were built to be used as support for the work.

In 1535 there was another religious apparition in Moratalla: this time the Virgin Mary (“la Rogativa”) appeared to a young shepherd named Ginés Martínez. The church of Santa María de la Asunción is now one of the most important monuments in the town, and it was in the 16th century that the most important extension work was undertaken on the building. The influence of the architects Francisco Florentino and Juan de Marquina can be seen, and the work was supervised by Pedro de Antequera. The ashlar stone was fashioned by the mason Juan Inglés, and in 1563 the walls of the square were built to be used as support for the work.

Of course, such an ambitious project required extensive funding, and due to the austerity of the Order of Santiago and the monarchy at the time, together with the stagnation in the town’s population, work had to be suspended at the end of the century. In 1598 the Order of Santiago ordered that work be stopped after 37 attempts to continue had faltered because of lack of funds, and the projected dimensions of the grand project were never reached. The building was finished with a mud wall, but work on the chapels and interior decoration continued throughout the 17th century.

Apart from the parish church there were eight other places of worship in Moratalla - Santa Ana, San Andrés, Santa Quiteria, La Soledad, San Antonio Abad, San Blas, San Nicolás and San Jorge – as well as the Convento de San Francisco and the Casa de Cristo. Religious associations, or brotherhoods, also proliferated, and some of them still exist today: the Cofradía de la Sangre, formed before 1549; the Santísimo Sacramento, which has been twinned with the equivalent association in Rome since the 16th century; the Santísimo Aparecimiento, founded after 1493; Santa Lucía (1596); La Soledad (1596); the Rosario (end of the 16th century); and Santa Ana, Jesús Nazareno y La Piedad, founded in 1607.

On 15th June 1621 the Miracle of Santísimo Cristo del Rayo took place, as recorded on page 105 of the 5th book of Baptisms. At three o’clock in the afternoon, so the story goes, the church bells were rung to warn of an approaching storm, and the inhabitants took refuge in the church while the rain and lightning fell all around. A flash of lightning came in through one of the windows and struck the image of Christ on the cross which was at the top of the main altarpiece, but no damage was caused except that the image was blackened. Neither was anyone inside the building hurt, and this was acclaimed as a miracle: since then the image has been known as the Cristo del Rayo.

On 15th June 1621 the Miracle of Santísimo Cristo del Rayo took place, as recorded on page 105 of the 5th book of Baptisms. At three o’clock in the afternoon, so the story goes, the church bells were rung to warn of an approaching storm, and the inhabitants took refuge in the church while the rain and lightning fell all around. A flash of lightning came in through one of the windows and struck the image of Christ on the cross which was at the top of the main altarpiece, but no damage was caused except that the image was blackened. Neither was anyone inside the building hurt, and this was acclaimed as a miracle: since then the image has been known as the Cristo del Rayo.

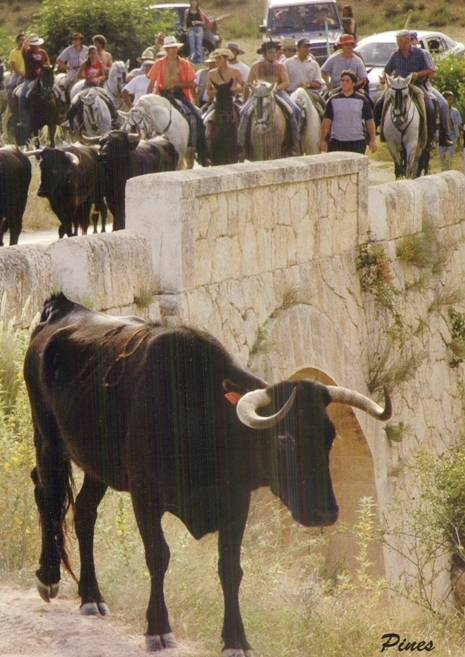

This gave rise to the popular “Fiestas de La Vaca” with bulls being run through the streets. The fiestas already existed, and had previously been held in the month of September during the town fair, but various social, economic and ecclesiastical factors combined to make it appropriate to move the date to June, dedicating them to the Cristo del Rayo.

At this time there were four hospitals in Moratalla, although they were not really hospitals in the modern sense of the word but rather homes for the poor. These were the Hospital de Santa Ana, which was run by the brotherhood of the same name, the Hospital de la Villa, in the street of the same name, the Hospital de La Soledad and the Hospital de la Casa de Cristo, which mainly looked after the pilgrims who journeyed to the Santuario, and disappeared when the Orden de la Merced took up residence there.

The Beginnings of Industrialization

Some of the industrial activity has hardly spread outside the immediate locality, perhaps due to the lack of natural communications routes, which has always been something of a handicap to the economy. Wood, wine, oil and esparto grass have all been produced locally and stayed mainly in the area, despite the construction of the Puente del Olmico, which leads out towards Caravaca. Despite these obstacles to trade, though, the forests in the municipality have made it an important producer of timber.

Some of the industrial activity has hardly spread outside the immediate locality, perhaps due to the lack of natural communications routes, which has always been something of a handicap to the economy. Wood, wine, oil and esparto grass have all been produced locally and stayed mainly in the area, despite the construction of the Puente del Olmico, which leads out towards Caravaca. Despite these obstacles to trade, though, the forests in the municipality have made it an important producer of timber.

The driving force behind the exploitation of the forests in the mountains of Moratalla was the “comendador” Diego de Soto. Through his political influence he obtained a timber monopoly, and even received special privileges from the Concejo of Murcia, where he sold wood for use in the construction sector. The authorities in Murcia also arranged for the road used by De Soto to be improved, and much of the timber was transported to the regional capital by river, down the Alhárabe and the Segura.

Later on French loggers arrived in the area to work in the forests, especially in the Sierra Seca, Revolcadores and Puerto del Conejo. On the one hand, the mountains were gradually deforested, but on the other this contributed to the development of industry in Moratalla. The proximity of the raw materials made it logical for sawmills to be established in the area, and despite various ups and downs there have been many in the municipality over the years. At the same time industry in the textile sector developed, and in the 18th century there were as many as fifty textile mills producing canvas and cloth for the navy and the fishing fleet, although this sector was always limited by the small amount of hemp produced locally. Another important area was the production of wine and liquor – there was a liquor factory in the 17th century, and two at the end of the 19th - and there were also olive presses and flour mills. Wine producers were generally family businesses, and most houses had a winery, but only those who produced large quantities traded it outside the area.

In 1900 a new initiative brought light to the town: this was the first electricity company, named La Eléctrica Moratallera, which was set up by locals using local capital, although it was later taken over by a larger company. The early years of the 20th century saw the beginnings of the “El Progreso” newspaper in the town, but cultural activity was still sparse. Well-known teachers abounded, including Inocencio Rodríguez, Domingo Abellán and Pedro García Aguilera, and the poets Elías Los Arcos, José Mª Lozano and Alfredo Marcos achieved a moderate degree of fame. The names of the Sandoval photographers and Fernando Sánchez López were also well respected, as were the historian Alfredo Rubio, the actress Estrella Gil and the singer García Guirao. Father Eduardo Rodríguez was a popular local religious figure.

In 1900 a new initiative brought light to the town: this was the first electricity company, named La Eléctrica Moratallera, which was set up by locals using local capital, although it was later taken over by a larger company. The early years of the 20th century saw the beginnings of the “El Progreso” newspaper in the town, but cultural activity was still sparse. Well-known teachers abounded, including Inocencio Rodríguez, Domingo Abellán and Pedro García Aguilera, and the poets Elías Los Arcos, José Mª Lozano and Alfredo Marcos achieved a moderate degree of fame. The names of the Sandoval photographers and Fernando Sánchez López were also well respected, as were the historian Alfredo Rubio, the actress Estrella Gil and the singer García Guirao. Father Eduardo Rodríguez was a popular local religious figure.

In 1917 the Teatro Trieta was completed, although it was originally named after Estrella Gil, and the tower of the parish church was erected in 1930-31. In the 1960s various fruit processing and canning factories were set up as local apricot production increased, but as the years went by most eventually closed down.

Moratalla’s Economic Difficulties

Probably one of the main obstacles to the economic and industrial development of Moratalla has been the lack of an efficient road network. When motor vehicles were introduced and new roads started to be built, the town was left behind and became isolated, and the rail network never reached the municipality. This in turn has always delayed the arrival of new technologies in the town, and the lack of effective industry has brought with it the collapse of small cottage industries. The years of dictatorship were hard for the town, which was largely depopulated as most of the male population left to seek agricultural work in France, sending money home to their families, and it was only when agricultural subsidies encouraged the plating of apricot, olive and almond orchards that the town started to recover.

Probably one of the main obstacles to the economic and industrial development of Moratalla has been the lack of an efficient road network. When motor vehicles were introduced and new roads started to be built, the town was left behind and became isolated, and the rail network never reached the municipality. This in turn has always delayed the arrival of new technologies in the town, and the lack of effective industry has brought with it the collapse of small cottage industries. The years of dictatorship were hard for the town, which was largely depopulated as most of the male population left to seek agricultural work in France, sending money home to their families, and it was only when agricultural subsidies encouraged the plating of apricot, olive and almond orchards that the town started to recover.

The late 20th century saw a belated surge towards modernization in Moratalla, with communications being improved, education being made universal and rural tourism being encouraged.

The rural environment was transformed, and more modern farming techniques were introduced, while industry was incentivized, particularly in the textile sector. At the same time the cultural and leisure activity in the municipality was broadened and many old houses were reformed and sold to city dwellers seeking the rural countryside, creating extra work in the services sector.

However, Moratalla still remains a characterful town, with an intact old quarter nestled beneath the castle and still depends largely on agriculture and rural tourism, the campsite and casas rurales attracting a steady stream of weekenders, particularly those drawn by the cool woodlands and outstandingly beautiful natural attractions which made Moratalla such an important location for the settlements of early prehistoric man in the first place.

article_detail

Contact Murcia Today: Editorial 000 000 000 /

Office 000 000 000